Igbo History and Origins

How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I]

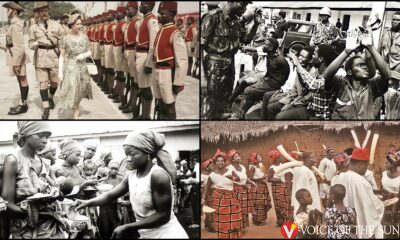

![How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I] How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland/Among The Ìgbò [Part I]](https://voiceofthesun.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/How-Igbo-People-Started-Becoming-Christians-181-Years-Ago-1841–2022-A-Brief-History-Of-Christianity-In-Igboland-Among-The-Igbo-Part-I-1.jpg)

Present-day Igbo Christian teenagers—including many young adults—raised strictly by Ìgbò Christian parents, and who have held steadfastly to the Christian faith, will hardly believe or know that Christianity was not anywhere known or heard of among the Ìgbò prior to 165 years ago when it came formally to Ọnịcha on 27 July 1857 or 181 years ago when it made its first inroad attempt in Abọ (today’s Ìgbò part of Delta State) in 1841. What they often know or presume is that Christianity is as ancient as the Ìgbò had existed, hence they are often appalled by the current growing wave of young and enlightened Ìgbò persons abandoning their Christian faith and returning to the indigenous traditional Ìgbò spirituality, otherwise broadly called Omenaanị or particularly, Ọdịnaanị.

This kind of presumption from among the young Igbo population was not so widespread about 30 years ago. The calculated withdrawal of historical activeness and consciousness from the mainstream Nigerian basic education as at 2 decades ago; the subtle unwillingness of the present-day orthodox Christian church authorities in Ìgbòland to constantly remind their congregants how, about over a century ago, European missionaries brought the faith they are currently expressing, and other possible factors, have combined to build the impression of these Ìgbò Christians who are teenagers and young adults, making them to never imagine that their ancestors were only formally and squarely Christianized not too long ago—a development that has sequentially resulted in their being Christians today.

The history of the Christianization of the Ìgbò people is as thick, tall, and entangling as the famed forests in which the people lived before colonization and its attendant urbanization and deforestation. As a notable historian of the Ìgbò, Professor Elizabeth Isichei asked in 1970:

Can one meaningfully reduce the almost infinite variety of responses in a society as various as Igboland, to a phenomenon as complex as the missionary impact?

The honest answer is ‘no.’ We can only tell the history of missionary impact among the Ìgbò as far as we know and have researched it in each generation. Sadly, the one large piece of the whole story that will continue to be regretted is the extremely deficient oral accounts of our ancestors who were the subjects of the Christianization experiment as against the towering, exhaustively written accounts of their ‘Christianizers’ (the missionaries). This imbalance of narratives/narrative sources leaves a lot of questions unanswered forever. Meanwhile, for more clarity within this context, I have collapsed the entire 181 years of Ìgbò Christianization journey/experience between 1841 and this year 2022 into three broad phases, relying mostly on very major turning points in history, such as wars and expeditions for their partitioning. As such, the following phases have emerged and will be discussed below:

- Phase One of Ìgbò Christianization (1841–1901)

- Phase Two of Ìgbò Christianization (1902–1970)

- Phase Three of Ìgbò Christianization (1971–2022)

It is important to have a basic mental geographical layout of Ìgbòland while engaging in the study of Ìgbò Christianization. This is because Christianity traveled from Europe to the Ìgbò through the two major waterways that bound the Ìgbò territory: The River Niger (locally called Oshimili Ọgbarụ) and the Cross River. These two awestriking water bodies gave rise to the earliest classification of the Ìgbò people into two broad groups which are:

- The Niger Ìgbò

- The Cross River Ìgbò

The Niger Ìgbò include all the Ìgbò on the eastern flank of the River Niger (i.e. the Ìgbò in the present-day Anambra, Imo, Rivers, Kogi, and Enugwu States of Nigeria, not excluding portions of Abia and Ebọnyị States) and the Ìgbò on the western flank of the Niger River (i.e. the Anịọma Ìgbò in the present-day multiethnic Delta State of Nigeria). The Cross-River Ìgbò include the Ìgbò people of Arọchukwu, Ọhafịa, Abịrịba, Bende/Item clan (in the present-day Abịa State) and of Ezaa, Ikwo, Unwana, Afikpo, Úbùrù, Ọkpọsị, Eda, etc., (in the present-day Ebọnyị State). As could be gleaned from any valid map of Ìgbòland, the Niger Ìgbò (both on the western and eastern flanks of the River Niger) occupy about 90% of the Ìgbò area while the Cross-River Ìgbò retain the remaining 10%. Indeed, the Christianization of Ìgbò people followed these same statistics, as we shall see in due course.

Phase One of Igbo Christianization (1841–1901)

![How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I] A TEMPORARY HOSPITAL, WATERSIDE ONICHA](https://voiceofthesun.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/How-Igbo-People-Started-Becoming-Christians-181-Years-Ago-1841–2022-A-Brief-History-Of-Christianity-In-Igboland-Among-The-Igbo-Part-I-2.jpg)

Thomas Fowell Buxton (1786–1845), a British businessman and ideologue, was unquestionably the chief genius behind the historic phenomenon we know today as the Christianization of the Ìgbò. The idea of bringing Christianity to the Ìgbò shores was principally the astute brainchild of Thomas Buxton but not without reasons or, more accurately, interests. It is claimed that this man, Buxton was a humanitarian who desperately wanted to see the end of the nefarious Transatlantic Slave Trade, especially on the west coast of Africa. Britain, his country, had profited from the notorious Transatlantic Slave Trade for centuries but resolved to abolish it—mostly because the country was becoming an industrial economy and had no more use for crowds of slaves in their space. Based on that coupled with pressures from humanitarians, Britain formally abolished the Transatlantic Slave Trade through the Abolition Act of 1807. However, the trade continued on the west coast of Africa for more than 25 years after the abolition. Buxton would learn that the slave trade had lingered on even more actively through the narrative published by Macgregor Laird and Richard Oldfield on their journey up to the Niger River between 1823 and 1834. Upon reading the narrative, Buxton’s mind was charged with an idea which can be summed thus:

Let us stop this slave trade by making these people Christians and also profit economically from it in return.

This singular idea would instigate historic changes among the peoples of West Africa. On the part of the Ìgbò people, it thrust upon them unprecedented and difficult transformations never seen before in centuries—chief of them being Christianization. Buxton’s technique theory for achieving the Christianization of the Ìgbò was thus in simple summary:

The bible and the plough: The bible representing the Christian God, and the plough representing trade in agricultural produce.

Buxton argued that as the Ìgbò (people of the Niger) would benefit from the sale of the Christian religion to them, so would Britain profit from trading “legitimately” on the Ìgbò shores. Also, as the argument went, the “legitimate trade” would enable the Ìgbò to profit legitimately rather than profiting illegitimately from the outlawed transatlantic slave trade. Buxton would later publish these and other arguments in a book by 1839. Through his persuasive arguments, the idea of the “Niger Expedition” was born together with the nationwide mobilization and awareness campaigns to realize it. Thus, the first expedition on the Niger (named “Niger Expedition”) was fixed for 1841.

The 1841 Niger Expedition simply meant a large-scale program of exploring the Niger area which included the Ìgbòland for the sole purpose of “civilizing” its indigenous peoples through Christianity and trade. And—if you may add more truthfully—the purpose also includes preparing a way for “civilizing” the same people through an impending colonial subjugation by the early 20th century. Ideally, a team had to be constituted for this assignment and it needed to be diverse, comprising of mainly merchants and evangelicals, in addition to technicians, medics, and other groups. By 12 May 1841, this team numbering some 170 men (including a few blacks and 162 whites), embarked on the three steamships named Albert, Wilberforce, and Soudan and set out from England to land on the Niger. They landed in August of 1841 and commenced negotiations with Obi Ọsai of Abọ and his council of elders on 27 August. While the trading group which formed the majority went about their business of negotiating and setting up trade, the Christianization group of the Church Mission Society (CMS) which formed the minority and had such persons like Rev. J. F. Schon (a German missionary and linguist), Samuel Ajayi Crowther (a Yoruba freed slave who was a catechist and later priest and bishop), and Simon Jonas (a church teacher and an Ìgbò freed slave) had some interactions with Obi Ọsai, the ruler of Abọ—an Ìgbò coastal town on the western flank of the River Niger.

There are a few things usually glossed over in the language nuances of this Christianization assignment, but which I consider critical for any Ìgbò person who dispassionately seeks to understand that past. Firstly, this team of over 170 men who landed at Abọ in Ìgbòland was not only called “Expedition Team” but “British Mission,” meaning that they were all expeditioners and missionaries, irrespective of their various statuses and roles. Expedition! Mission! So, what does it mean to expedite? What was to be expedited? And, on the other hand, what does it mean to be on a mission to missionize? Who were they to missionize? The answers to these compelling questions lie in the theory of Thomas Buxton in whose mind germinated the idea of Christianizing (missionizing) the Ìgbò as well as expediting legitimate trade with them—the chief interest leaning on the trade and the enormous economic potentials it promised for Britain. As such, both the CMS agents and the traders were all on the singular mission of advancing and achieving the paramount interest of the British in Ìgbòland which was fundamentally material, and could only be sustained for a longer time by Christianizing (civilizing) the people. Secondly, the overall message of this mission was articulated in brief but very consequential words, among other charges, both for the missionaries and traders. Those instructive words of the government which the leaders of the expedition were to tell the [Ìgbò] people on the Niger were thus:

“…that the Queen and the people of England profess the Christian religion; and that by this religion they are commanded to assist in promoting goodwill, peace, and brotherly love, among all nations and men; and that in endeavoring to commence a further intercourse with the African nations, Her Majesty’s Government are actuated and guided by these (Christian) principles.”

The instruction above subliminally implies that the people [Ìgbò] are to participate “in promoting” a trade relationship between themselves and the British—a relationship that must follow Christian principles and not Ìgbò [the peoples’] principles.

Meanwhile, the leader of Abọ, Obi Ọsai was excited to establish a relationship with the team. He was reported to have requested that Simon Jonas, the CMS church teacher on the team stayed back to teach his people how to read and write. He was even reported to have signed treaties of trade with the merchants in the team. Ọsai’s interest was not the gospel of Christianity but the wonder of seeing a black person (Simon Jonas) like him and his people being able to read and write—an ability he had thought only a white man could possess. Unfortunately, this team lasted barely a month on the Niger before malarial fever descended on them, killing off 62 of them—all whites—before they could reach England in a hurried return. It was a devastating experience for Buxton, the genius behind the expedition, the government, individual sponsors, and the people of England [Britain]. In a space of four years after the failed expedition, Buxton was dead from the rude shock the tragedy gave him, coupled with the humiliation and outrage it generated nationally in Britain. To speak of expedition or Christianization of the Ìgbò people of the Niger in Britain at the time was similar to desiring suicide. And so, it seemed that Thomas Buxton’s genius and vision for the Christianization of the Ìgbò was to be laid to rest with him forever.

However, like most powerful ideas (even among terrorists and evil men) that never die until they test some breath of life, Buxton’s idea of Christianizing the Ìgbò was to find fecundity in the mind of the CMS Secretary at the time, Rev Henry Venn—not excluding a few other persons and groups who tenaciously believed in it and a second trial. The second trial at the expedition on the Niger would happen 13 years later in 1854. It was used to test the waters after re-planning and re-strategizing for about 12 years, hence it was a brief one. The final and successful expedition which sealed the Christianization of the Ìgbò was the famous 1857 Niger Expedition which did not have to be dominated by the whites but by the blacks, as they (blacks) were adjudged, among other reasons, able to withstand the tropical climate more than the whites. In fact, unlike the white-dominated 1841 team, the 1857 expedition team comprised 12 Europeans (whites) and 53 Africans (blacks). This change of strategy gave rise to the popular expression “Africa for the Africans” among the CMS authorities in London. Nevertheless, a white man led this 1857 Expedition Team in the person of Dr. William Baikie but was actively assisted by Rev Samuel Ajayi Crowther who would later become a bishop. Baikie oversaw the establishment of trade while Crowther oversaw the establishment of mission. The next important person and pioneer missionary that began the real work of Christianizing the Ìgbò was no other than Rev John Christopher Taylor, a descendant of Ìgbò slaves who were repatriated to Sierra-Leone early in the 19th century. He joined the CMS and was later ordained a priest. He was appointed the pioneer head of the Ọnịcha Mission assisted by church teacher Simon Jonas who did not last long in the mission work before he died in the early 1860s.

Contrary to the 1841 Expedition, Ọnịcha rather than Abọ, became the preferred center for the establishment of mission and trade on 27 July 1857. Geographical and political considerations led to this change of location, as strongly recommended by Crowther. In Crowther’s instruction to Taylor, he had emphasized:

“The first and most important place to which your attention should be chiefly directed is Ọnịcha, which appears to be the high road to the heart of the Ìgbò nation.”

Indeed, Crowther was quite smart in his calculations. And for his smart choice of Ọnịcha as the gateway to the Ìgbò heartland, the Christianization of Ìgbò people would later be assured. As for trade, of course, the same Ọnịcha determined and has continued to determine and control the economy of the Ìgbò both within Nigeria and beyond. By this time, Obi Ọsai of Abọ had died in 1854 and Crowther could no longer trust his two sons who succeeded him in ruling Abọ. Also, swaths of Ọnịcha land were much drier than those of Abọ which often get swamped during the rainy season. These considerations culminated in the choice of Ọnịcha as the cradle of Ìgbò Christianization as well as formal and forced integration of Ìgbòland into the Western economy/market via British trade.

The CMS station in Ọnịcha, having been set up, the Christianization of the Ìgbò was embarked on through conversion. Crowther’s charge to Taylor read:

“Your ministerial duties will be very simple and plain; you shall have to teach more by conversation when you visit the people or they visit you at the beginning than by direct service.”

As expected, Taylor set out with great zeal to Christianize the Ìgbò people of Ọnịcha. They had welcomed him as “one of their own,” considering his skin color. In fact, Taylor and his Sierra-Leonean assistants were popularly identified as “Oyibo Oji” (black Englishmen)—a derisive slang for blacks pretending to be whites. The Obi of Ọnịcha at the time, Obi Akazụa was quite benevolent to the Mission. It was he who gave the missionaries the large parcels of land where they settled and from which they leased some portions to the Roman Catholic missionaries when they arrived 28 years later in 1885. The situation of the Christianization mission from 1857 up to 1870 can be best described as wobbly, complicated, and consistently troubled. Rev Taylor sometimes appeared energetic and successful in his missionary evangelism but would slump to the deepest frustration and despair the next moment. Not only was he fighting almost fruitlessly to overthrow the social order in Ọnịcha and replace it with Christian and British structure, but he was also having internal fights with his junior colleagues who either embarrassed or challenged his leadership authority. Taylor mistook the hospitality of Ọnịcha people to be a total disposition to the message of Christianity without understanding the political undertones it carried subtly with it. Ọnịcha, for a fact, was at war with its neighbors, including Ògídí and Obosi; and so, it desperately needed allies, local or foreign, especially to scare off their enemies from the interiors. The missionaries and traders were a good answer to their desire for alliances to ward off enemies.

Rev Taylor made converts and had, within a decade by 1867, only about 310 members in his church amidst a general Ọnịcha population of over 21,000 persons (see F. K. Ekechi’s Missionary Enterprise and Rivalry in Igboland, 1857–1914). It was an extremely small number for such a long time. But there were other achievements. Taylor established the very first formal primary school in Ìgbòland which was opened at Ọnịcha on Monday, 15 November 1858 with a total of 14 girls aged between 10 and 16 years. Boys considered it degrading to go to school at the time until some began to see the benefits it promised, such as the art of reading and writing. It has to be established here that the idea of a “boarding school” in Ìgbòland was also planted by Taylor when he assembled these school children and kept them in the mission house to ensure that they were kept away from the “pagan environment.” With the boarding school, children were effectively Christianized such that they could hardly return to the indigenous spirituality of their parents when they had grown. It worked! They were called “boarders” and were supported with funds and material items (like discarded clothes, writing, and reading materials, etc.) that came from Britain through Taylor’s solicitations. It was from among these early “boarders” arose such early educated Ọnịcha Christian men like Isaac Mba, T. D. Anyaegbunam, and others, including Walter Amobi of Ogidi who would later help in bible translations and missionary expansion into the Ìgbò interiors when they had become full adults by the end of the 19th century. The subjects they learned in the boarding school included Bible stories, Prayers, Music, Arithmetic, Geography, and English. There is no question that what attracted these Ìgbò at the time to the Christianization scheme was more of the desire to learn how to read and write in the white man’s language and barely the message of Christianity. It was the reason some parents allowed their children to join the boarding school after seeing other children march through the town singing songs. This led to a great increase in enrolment by 1864. Taylor also tried in vain to discourage his converts from polygamy, especially the prominent ones like John Okosi. He ended up making Okosi return to the indigenous faith as well as to his many wives. It has to be noted that Okosi was one of the precious converts Crowther and Taylor boasted of because he was, unlike most of the converts who were the rejects and downtrodden of the society, from a privileged background. With men like Okosi as members of the congregation, the missionaries reasoned, other prominent people could be Christianized and the church would not just be filled with only slaves and rejects. Thus, when Okosi de-Christianized to be able to return to his polygamous married life, Taylor received it with a heavy heart and made the rash, immature decision of dismissing Okosi’s son, Gilbert from the mission boarding school.

Meanwhile, Taylor still fought battles in the Mission. As a result of the internal crises between Taylor and his junior colleagues, he ran into problems with Bishop Crowther whose son had done a shabby job of investigating the causes of conflict between him and other mission agents much to the disfavor of Taylor by the late 1860s. Thus, by 1869, Taylor was transferred from Ọnịcha and replaced by his biggest rival, Rev W. G. Romaine. Records of success at Christianization would dwindle as scandals, epidemics, inter-village wars, and political conflicts between the traders and Ọnịcha indigenes overtook the airwaves throughout the 1870s. For example, between 1876 and 1877, one of Taylor’s successors, William John, from Sierra Leone, ruthlessly flogged two girls whom he and his wife kept as slaves and inserted pepper into their genitals as a way of punishing them further. When one of the girls died from the pain and exhaustion of the punishment, John and his wife secretly buried her. But the criminal act came to light and tremendously scandalized the people and the Mission. The trading group of the Expedition Team used the Court of Equity to diminish the enormity of this crime by not doing a thorough investigation, hence, John went free until many years later when he was re-arraigned, found guilty, and jailed in Sierra Leone. The 1870s, however, were the period of the CMS expansion into other Ìgbò areas beyond Ọnịcha. The Christianization drive, having been tested for 17 years in Ọnịcha, was carried into riverine areas like Osomala in 1873, Asaba in 1874, Abọ in 1883, and Obosi in 1882.

The 1880s were to be the beginning of the fierce competition, rivalry, and political maneuvering between the two main Christian missions that established their enterprise in Ìgbòland, and also between the whites and blacks in the CMS in particular—all in the battle for the mind and material resources of the Ìgbò through Christianization. Thus, on 5 December 1885, the missionaries of the Roman Catholic Mission arrived in Ọnịcha to establish their own enterprise under the aegis of the Holy Ghost Fathers (otherwise called “CSSp.” a Latin short for Congregatio Sancti Spiriti) – a French mission led by Fr Joseph Lutz. A year before, in 1884, the RCM had already been established in Asaba (on the western flank of the Niger River) under the aegis of the Society for African Missions (SMA), an Italian mission led by a Milanese priest, Fr Carlo Zappa who would eventually spend a long time among the West Niger Ìgbò. No sooner than the missionaries of RCM settled down and began winning converts in Ọnịcha did they begin to face opposition from the CMS. In reality, the RCM had deeper pockets and a heavier financial war chest than the CMS to run the missionary enterprise.

These missionary enterprises were, beneath the surface, capitalist ventures of Europe, for they were eventually going to recover in the distant future all they had spent in innumerable folds.

With their robust finances, the RCM agents were able to attract and absorb many of the church teachers and catechists of the CMS into their fold. An entire congregation of CMS converts in Osomari [Osomala] was led by one Jacob Akubeze (a CMS church teacher) to switch over to the RCM when his hands had been well-oiled by the missionaries of RCM. Another method deployed by missionaries of RCM in winning many converts within a short time was the purchase of slaves which they extensively embarked on before they changed strategy by seeking out noblemen they considered seducible. One of such men was Idigo of Aguleri who received a seductive gift of a horse from them as a support for his Ọzọ ambition. Idigo fell completely flat for it. He broke the laws of his clan, and for fear of attack from his clansmen who warned him not to entertain the strange religion among them, ran away. With the RCM support, Idigo went and founded a ‘Christian village’ with his large family in an unoccupied land within Agụleri by 1890. It was from among his Christian village that the first Catholics and early educated people in Agụleri were drawn. Idigo’s descendants, today, claim to have come from a “royal” lineage of about 500 years when their patriarch had only escaped from the heart of Agụleri to establish another settlement just 132 years ago! During this period also, the first attempt at Christianizing the Ìgbò of the Cross River was made in 1888 when the United Free Church Mission, alternatively known as “Presbyterian” established, rather passively, a mission at Unwana in today’s Ebọnyị State. The Presbyterian mission among the Cross River Ìgbò did not thrive until the beginning of the 20th century.

The 1890s were to mark the last decade of the struggling attempts to Christianize the Ìgbò in the 19th century. The rivalry between the CMS and RCM had continued as both enterprises began moving 5 to 30 miles into the interiors of Ìgbòland from Ọnịcha. This launch into the interiors began to happen—more decisively—only when the two missionary enterprises were now completely dominated by white men and women, some of who were racists too. On the part of the CMS, the black Africans from Sierra Leone who were mostly of Ìgbò parentage and who were locally called “oyibo oji” had tilled the soil of the enterprise for some 3 decades, but were now considered incapable of running it, especially to match the all-white-led RCM, their rival. In sum, the CMS authorities at the Headquarters in London embarked on what would later be known as the “Root and Branch Reform” by sending in scores of fire-spitting, energetic, university-educated young white missionary men and women from 1890s to 1910s to Ìgbòland east of the Niger. Some of the notable ones included Henry Dobinson, Thomas John Dennis (together with two of his siblings, Fanny and Edward), Edith Warner, Herbert Tugwell (Bishop), Sydney Richard Smith, George Thomas Basden, Mary Elms, and others. Most of these aforementioned spent not less than 20 years among the Niger Ìgbò and were able to effectively Christianize the people later in the 20th century! This radical team of white CMS agents would match the RCM fire for fire in the fight for the Ìgbò mind as the new century drew close.

Meanwhile, Bishop Crowther would die in the early 1890s from the racist humiliation he received from the young white evangelicals. The 1890s proved also a turbulent period for the white zealots who had arrived with pomp, in their words, to conquer and overthrow the Ìgbò society for their lord Jesus Christ. They could not have possibly marched freely through the Ìgbò territory without encountering fierce resistance. On the western flank of the River Niger where the West Niger Ìgbò territory was, there was a growing discontent against these missionaries and their efforts to Christianize the people which resulted in the overthrow of the traditional order. To contain these unwanted events among them, a dreaded secret society famously known as Ekumeku was formed in the town of Ìgbò-Ụzọ (erroneously spelled “Ibusa” in today’s Delta State). Ekumeku, as some have conjectured, is a corrupted version of Ekwunekwu which implies, in Ìgbò language, the imperative of “speak nothing” or “do not reveal!” Within a short time, the Ekumeku movement spread to other parts of West Niger Ìgbò territory. And by 1898, the movement attacked mission establishments at Isele-Uku, Illa, Ebu, Ezi, Ọkpanam, and Ìgbò-Ụzọ. The missionaries were deeply frightened and called on the Royal Niger Company (the British Government body representing the trading group) to intervene with their military expeditionary forces. One Egbosha, an insignificant character in the Isele-Uku society who had become acquainted with the white man as a convert of the RCM, facilitated the intervention. Through his compliance, the SMA (Society for African Missions)-RCM under Fr Zappa intimated one Major Festing, a soldier and arch-Roman Catholic of the Ekumeku secret society. According to Professor Ayandele, Festing “led a force of well-disciplined troops officered by six Europeans and punished the Ekumeku in a manner similar to the punishment inflicted upon the Ijebu. [Thus] Egbosha was confirmed on his throne at Isele-Uku.”

Characters like Egbosha who were nobodies in the traditional society but who smartly took advantage of the situation to become important by submitting to Christianization, acquiring some literacy in mission primary schools, and working for the missions and/or trading companies were scornfully referred to as enu oyibo (the “emergency new men” who were made by Oyibo [the whiteman]). On the eastern flank of the River Niger, such men abound among the Ìgbò, and they include persons like Walter Amobi of Ògídí, Kọdịlịnye of Obosi, Idigo of Agụleri, Onyeama of Eke, among others. Interestingly, these “enu oyibo” men produced descendants who were regarded as socially and materially successful families in the Ìgbò society throughout the 20th century and even now. This phase of Ìgbò Christianization came to an end by 1901 when the white missionaries in Ìgbò territory—in cahoots with their colonizer-brethren who had set out since 1885 invading Africa and partitioning it into their colonies—encouraged planned military expeditions as the quickest solution to resisting the “civilization” their forebears, led by Thomas Buxton, had charged them to bring to the Ìgbò and other Africans principally via Christianization.

Conclusion

This first phase of Christianizing the Ìgbò people was a long and tedious one lasting about 60 years. As we have examined so far, the phase was marked by many trials and errors, instabilities, confusion, chaos, crises, and anxieties, all of which prove that the Christianization program was unsuccessful within the said period, judging by the number of resources and long years expended. The Ìgbò were not going to allow themselves to be Christianized by strangers in their territory. More than 90% of them would rather take advantage of the material offers and promises made by missionaries while remaining loyal to the traditional spiritual systems. Despite their overall dense population of the Ìgbò running into hundreds of thousands at the time, the zealous missionaries—CMS, RCM, and Presbyterian combined—could not make a thousand of them Christians in all of 60 years between 1841 and 1901. Naturally, this implied that success was very slow. On the other hand, it was expected also to slow down the pace of trade which was the economic—and major—arm of the civilizing mission. As such, something decisive, even ruthless, radical, and sweeping needed to be done to hasten progress. That? The bloody military expeditions in Ìgbòland began with Arọchukwu in today’s Abia State in November 1901. That is where the second part of this history series would begin. That is the second phase of the Christianization of Ìgbò people.

This Phenomenal Historical Piece Was Written By Chijioke Ngobili For Voice Of The Sun

Please Support and DONATE To Us. Help Us In Preserving Our History, Culture and Beliefs as Ndi Igbo. CLICK HERE to assist us financially.

-

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years ago

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years agoThe Four Igbo Market Days and Their Significance In Odinala na Omenala ÌGBÒ

-

Igbo History and Origins2 years ago

Igbo History and Origins2 years agoNnamdi Azikiwe: Legacy of a Nigerian Nationalist And Igbo Icon

-

Igbo News3 years ago

Igbo News3 years agoIgbo Land Is Not Landlocked – We Have The Deepest And Shortest Access To The Atlantic Ocean

-

Igbo Spirituality2 years ago

Igbo Spirituality2 years agoÌgbò Ancestors Did Not Worship Idols and Demons – A Journey Into Ịgọ Mmụọ In Odinana Ìgbò

-

Igbo Cultures And Traditions2 years ago

Igbo Cultures And Traditions2 years agoWhich Igbo Market Day Is Today – Get The Complete Igbo Calendar

-

Igbo Spirituality2 years ago

Igbo Spirituality2 years agoUnderstanding Ndị Ịchie In Igbo Cosmology: Who Are Ndi Ichie In Odinana na Omenana Ìgbò?

-

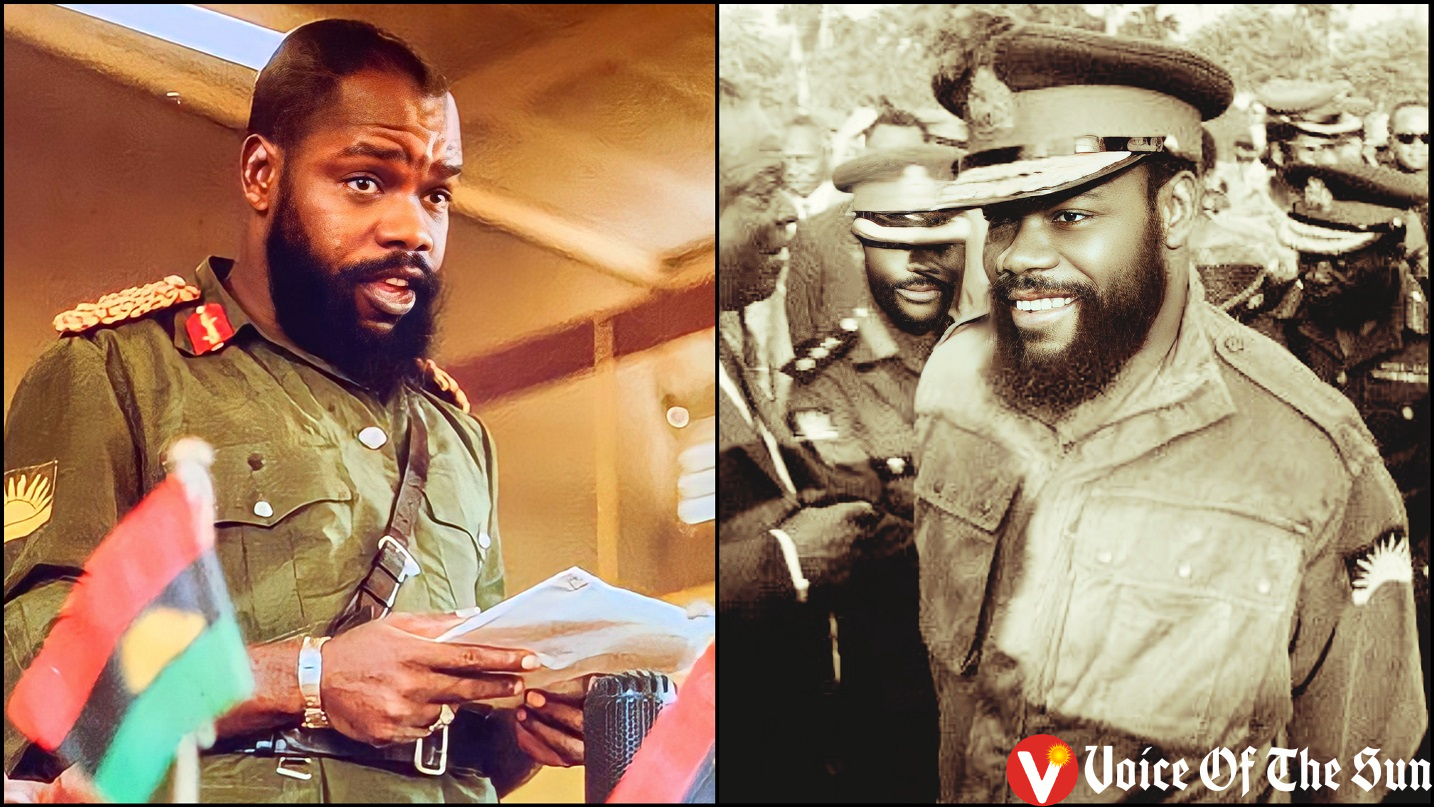

Igbo History and Origins2 years ago

Igbo History and Origins2 years agoChukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu: The Life And Legacy Of An Igbo Hero

-

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years ago

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years agoThe Cultural and Spiritual Importance of Nzu in Ìgbò Odinala na Omenala

Afamefuna

June 3, 2023 at 10:41 am

Aka olu gi amaka. Jisie ike!

How could I get access to the part 2 and 3 of this wonderful piece?

Voice Of The Sun

June 22, 2023 at 8:31 pm

Dalu rinne nwannem.. We are working on the accompanying parts of the article… You can follow us on Facebook to know when they will be available.