Igbo History and Origins

How The British Gradually Broke Apart The Indigenous Economic System Of Ndị Ìgbò

A Bird’s Eye View On How The British Gradually And Softly Broke Apart The Indigenous Economic/Financial System Of Ndị Ìgbò To Introduce Theirs Beginning With The Military Expeditions

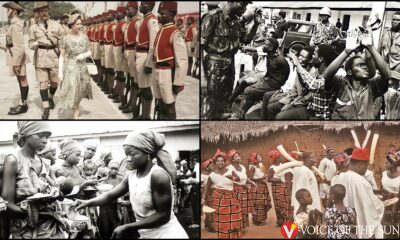

While the British forces invaded and raided Ìgbòland from 1901 through 1919, they massively had in their employ, black men, who were also soldiers drawn from the North (the Hausa soldiers formed by Capt. Glover in Lagos) and other Southern areas.

Prof. Elizabeth Isichei, the historian, totaled the number of European officers (whites) during the Arọ expedition which was the first assault on Ìgbòland at about 70 and the blacks at 3,464 — such a margin of black men joining in killing fellow blacks like it would happen again between 1967-1970!

Perhaps, these blacks were coerced to do so. Perhaps, they were also excited to be called to do so. One cannot fully tell. Be that as it may, it is pertinent to understand that the over 3,000 black men who were part of the expedition/s were not all soldiers. In fact, about 50% were employed as “carriers”.

Carriers, to be simply put and collectively defined, were men who were either carrying the white men on hammocks on their shoulders for several miles on the land, or carrying the white men’s loads on their heads or carrying other arms accessories, either on the head or on the hand to different destinations. Essentially, they were a collection of helpers for the soldiers who fought on the battlefront.

Surprisingly, after the first expedition which is the Arọ expedition, the British craftily embarked on adding the Ìgbò to the collection of carriers. Most of them were young men in their 20s and 30s and were probably excited or curious or even coerced to do the job of carrying stuff for the African and European soldiers assaulting the Ìgbò communities.

In Ụnwana, around Afịkpo (Ehugbo), 250 carriers were recruited for attacks on other communities. The British soldiers considered Ụnwana people as “friendly” (as evidenced in Prof S. N. Nwabara’s book, Iboland: A Century of Contact With Britain: 1860-1960). But the employment of these carriers was more than the purpose of the face value. It was strategic. A British soldier, Major Heneker who led one of the assaults had revealed that the carriers, after the expedition, would (in his words):

“…form a nucleus in each tribe of men experienced in the white man’s ways, and having been well treated, their influence is in our favor, and tends greatly to establish confidence in us”.

Prof Nwabara rightly establishes that these carriers were paid handsomely with the coin currency. They were expected, after the expeditions, to return to their communities and “spread the coin currency among their people by spending their wages”. This was not only done to the Ìgbò but to their neighbors of Efik, Ịjọ, Igala, etc.

The earliest circulation of the British coin currency in Ìgbòland which would later be known as “kobo-kobo/Afụ-afụ” was to be spearheaded by these carriers who also served the missionaries hugely early in the 20th century. The CMS Ọnịcha had a yearly budget for payment of carriers who carried missionaries on hammocks as well as their loads across several bushes and rough terrains.

It was this mass of carriers that majorly premiered the introduction of the British coin currency in Ìgbòland as well as its fascination which compelled our people to name it “ego bekee/ego oyibo”. This economic penetration, funny enough, is reflected in the names some parents gave their children at the time, such names as: “Egoyibo”, “Egocha”, etc.

Perhaps, the parents who named their children such names were long-time carriers who had received huge pay from their services and were able to grandstand around as “ndị ji ego oyibo” in their communities. Unknown to them, they were ensnared of a systemic impoverishment in the years and decades that were to come, especially in the late 1920s which culminated in the economic frustration that led to the Aba Women Revolt of 1929.

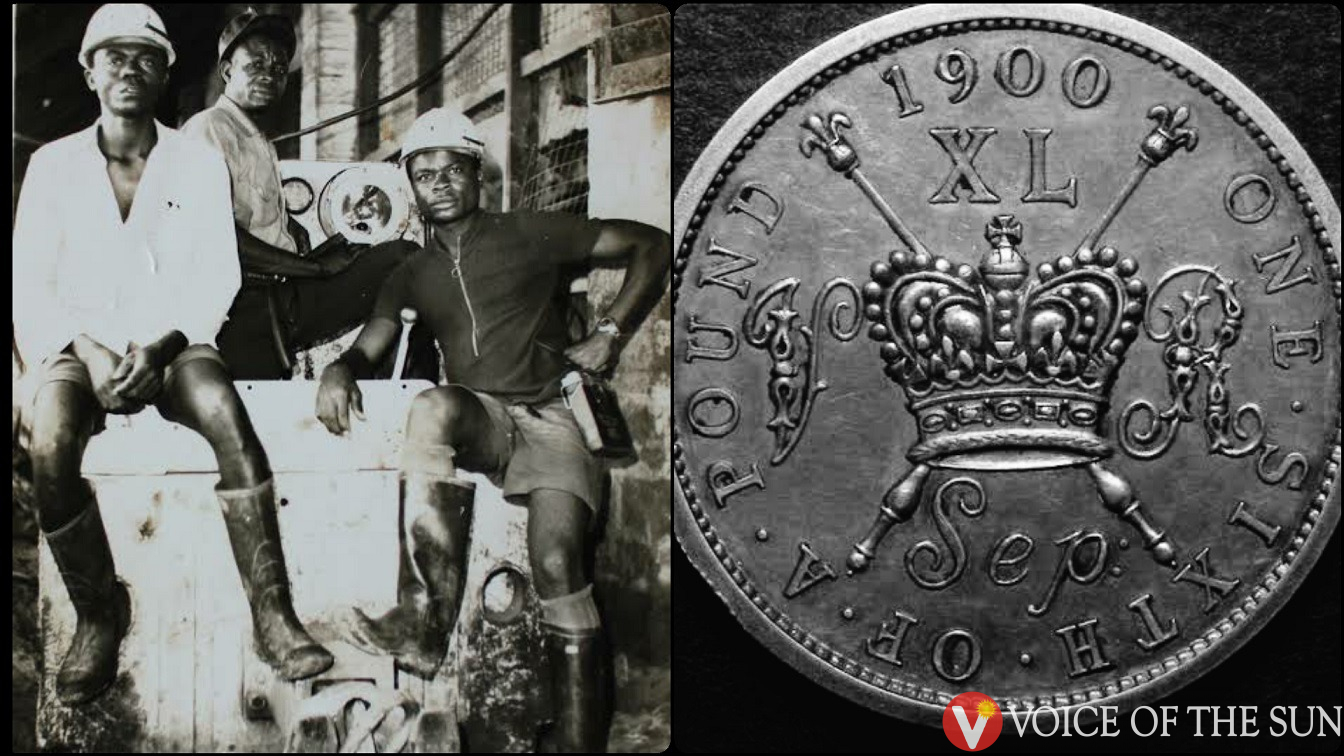

From my personal studies and research, the final assault on Ìgbòland that broke down the indigenous economic/financial system completely, was the beginning of the mining of coal in Enugwu from around 1915 when the first mass of miners from Ọnịcha led by one Alfred (one of the colliery camps in Enugwu is named after him as ‘Ugwu Alfred’) arrived Enugwu for the first mining activities (Cf. Elizabeth Isichei’s A History of the Ìgbò People).

With the growth of the miners into hundreds, the wages were paid in the British coin currency and the miners spent and spread it across the Ìgbòland, mostly the Enugwu, and Anambra areas. Somehow, I have a feeling that this could be one of the taproots of how many people from the Anambra areas acquired huge capital that launched them into businesses ahead of other parts of Ìgbòland in the first half of the 20th century.

Indeed, while the British had militarily forced its political authority on Ìgbòland, they tactfully, cunningly, and strategically imposed their economic system on Ndị Ìgbò devoid of physical force. Of course, the social and cultural impositions had begun quietly in the late 19th century through the auspicious zeal of the missionaries.

Unfortunately, only a few of our ancestors then saw this grand invasion and imposition plan coming to fulfillment. The rest were too shocked to even process the events that happened at a fast pace at the time.

Ndị Ìgbò ga-echigha azụ na ntọana ndị mbụ na ndị Egede wubere n’Omenaala ma ọ bụrụ na ha ma na ha ga aga n’ihu tọrọ atọ dịka mba Izrel si wee mee.

©Chijioke Ngobili, 2020

This Article Was Written By Chijioke Ngobili

Editor’s Note: We are dedicated to providing factual reports of history, news, opinions, and discussions on the people of the South-East of Nigeria. We are open to questions, contributions, and corrections on the topics we chose to share. Please feel free to drop your comments below, or send us an email at [email protected]. We promise to attend to your inquiry, reply to you and act on your request within a week. Please also endeavor to share our publications, to help us reach more of our people.

-

![How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I] How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland/Among The Ìgbò [Part I]](https://voiceofthesun.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/How-Igbo-People-Started-Becoming-Christians-181-Years-Ago-1841–2022-A-Brief-History-Of-Christianity-In-Igboland-Among-The-Igbo-Part-I-1-400x240.jpg)

![How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I] How Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland/Among The Ìgbò [Part I]](https://voiceofthesun.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/How-Igbo-People-Started-Becoming-Christians-181-Years-Ago-1841–2022-A-Brief-History-Of-Christianity-In-Igboland-Among-The-Igbo-Part-I-1-80x80.jpg) Igbo History and Origins3 years ago

Igbo History and Origins3 years agoHow Igbo People Started Becoming Christians 181 Years Ago (1841–2022): A Brief History Of Christianity In Ìgbòland [Part I]

-

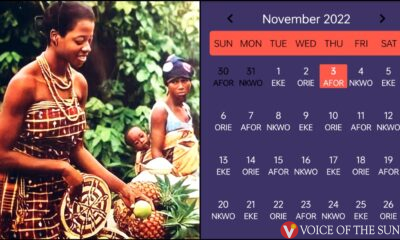

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years ago

Igbo Cultures And Traditions3 years agoThe Four Igbo Market Days and Their Significance In Odinala na Omenala ÌGBÒ

-

Igbo History and Origins2 years ago

Igbo History and Origins2 years agoNnamdi Azikiwe: Legacy of a Nigerian Nationalist And Igbo Icon

-

Igbo News3 years ago

Igbo News3 years agoIgbo Land Is Not Landlocked – We Have The Deepest And Shortest Access To The Atlantic Ocean

-

Igbo Spirituality2 years ago

Igbo Spirituality2 years agoÌgbò Ancestors Did Not Worship Idols and Demons – A Journey Into Ịgọ Mmụọ In Odinana Ìgbò

-

Igbo Cultures And Traditions2 years ago

Igbo Cultures And Traditions2 years agoWhich Igbo Market Day Is Today – Get The Complete Igbo Calendar

-

Igbo Spirituality2 years ago

Igbo Spirituality2 years agoUnderstanding Ndị Ịchie In Igbo Cosmology: Who Are Ndi Ichie In Odinana na Omenana Ìgbò?

-

Igbo History and Origins2 years ago

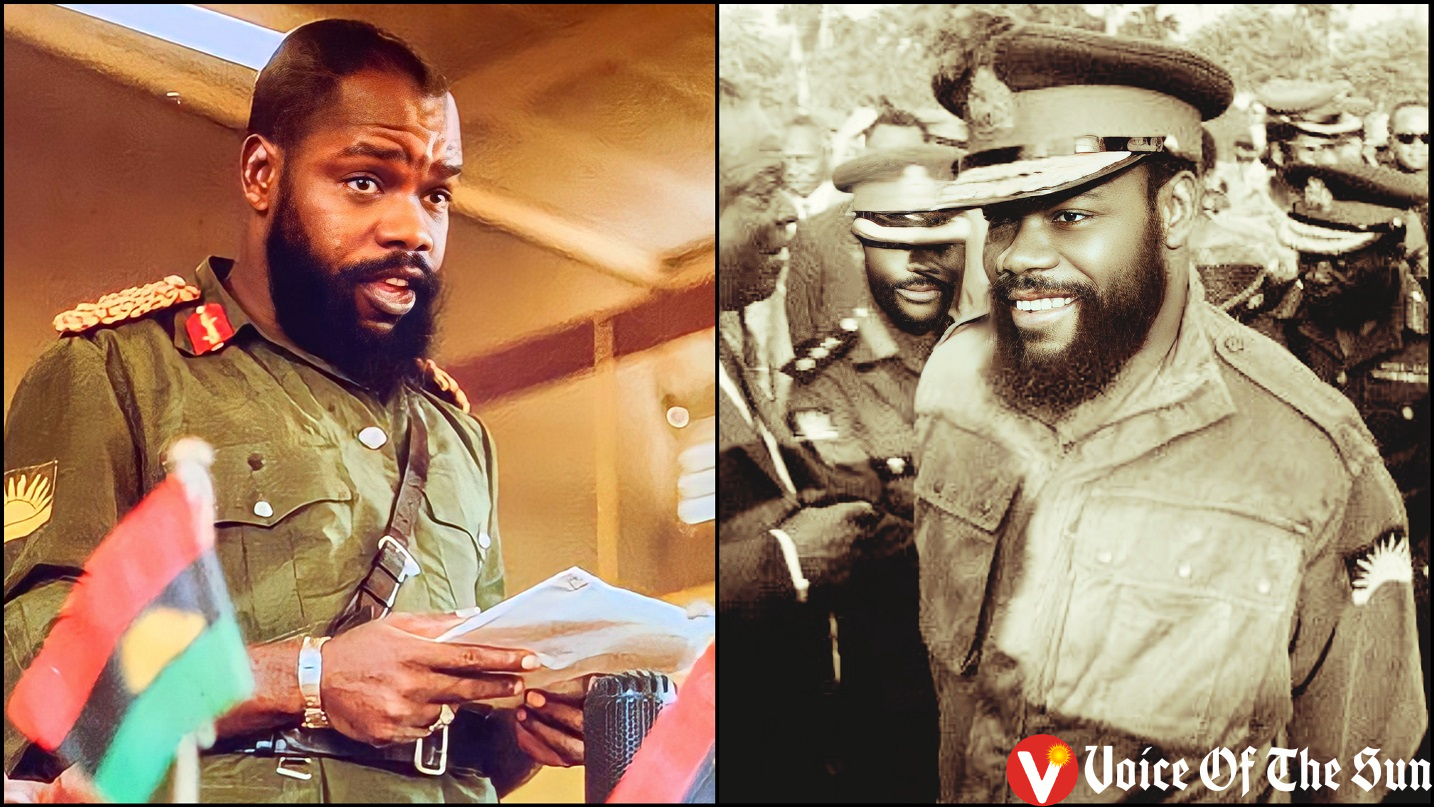

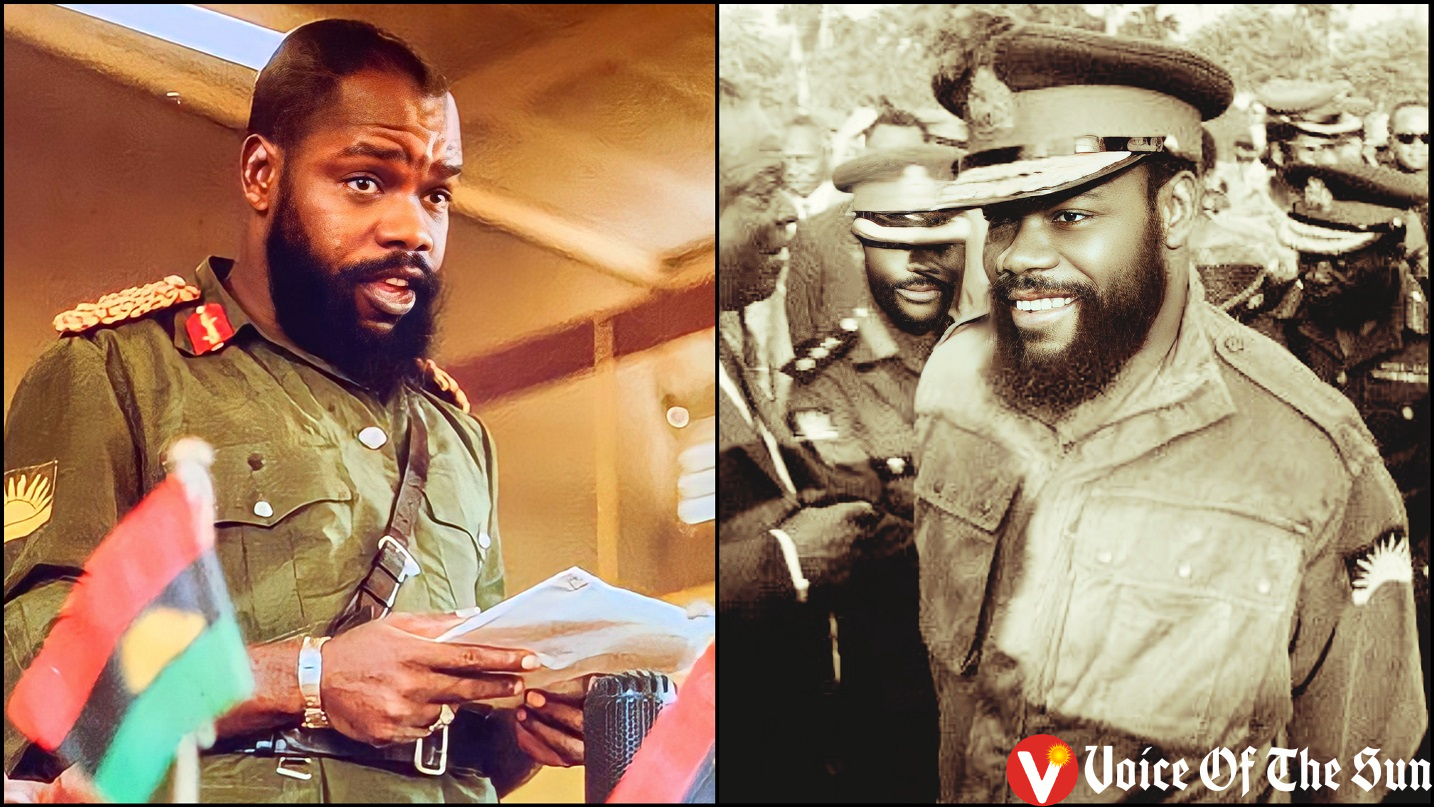

Igbo History and Origins2 years agoChukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu: The Life And Legacy Of An Igbo Hero